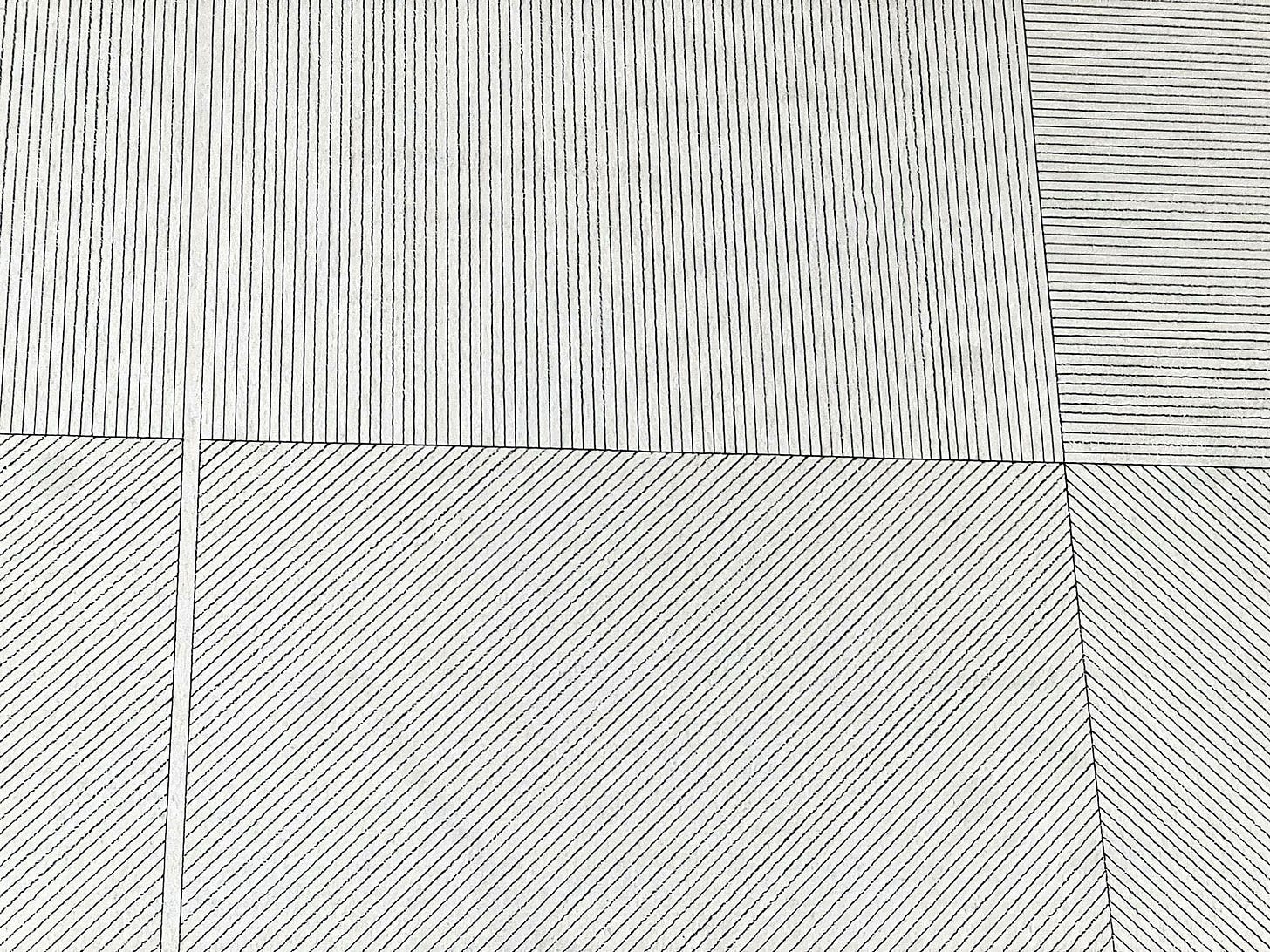

Last week at SFMOMA, I saw a piece of art called “Wall Drawing 1” by Sol LeWitt. It was a grid of carefully drawn lines. But it wasn’t on a canvas. It was drawn directly on the wall.

I thought to myself, “that’s one way to make sure the museum never moves your piece out of rotation!”

But then I read the placard explaining the piece and discovered that while Sol LeWitt was credited with the piece, he, in fact, did not actually draw it. It credits LeWitt as drawing the original piece but this particular one was drawn by another artist who followed the detailed instructions LeWitt left behind before he died.

This got me thinking about something big.

What makes art, art? The idea behind it? Or the actual making of it?

When we say "that's a LeWitt" for something he never touched, what are we really valuing?

This question isn't just about fancy museum art. It touches on everything from digital art to photography to music to those NFTs everyone was talking about a few years ago.

"The idea becomes a machine that makes the art."

When Instructions Become Art

Back in 1968, LeWitt wrote something revolutionary: "The idea becomes a machine that makes the art."

This was pretty wild thinking at the time.

For centuries, we praised artists for their skilled hands—the way Rembrandt painted light or how Michelangelo carved marble. But LeWitt flipped this idea upside down. He suggested the concept itself was the art, while the physical thing was just one version of that concept.

LeWitt would write detailed instructions like: "Draw straight lines from wall to wall, spaced 1 inch apart, covering the entire wall." Then someone else would follow these instructions to create the actual drawing.

Think of it like a recipe. The chef who creates the recipe is still credited, even when other people cook the dish.

From Museum Walls to Computer Screens

This approach feels surprisingly modern today.

Consider digital artists who create images using computer programs. They're not directly touching paint or canvas. They're creating instructions (in the form of computer commands) that generate visual results.

The real creative work might be in setting up those instructions, not in pushing the final "print" button.

It's similar to how LeWitt worked:

LeWitt: "Draw these specific lines in this pattern using these colors."

Digital artist: "Create these shapes with these effects in this arrangement."

Both are creating sets of rules rather than doing all the physical work themselves.

Asking Computers to Make Art

This brings us to those AI art generators you've probably heard about ad nauseam lately.

When someone types a description into a generative AI tool, they're basically giving instructions: "Show me a sunset over mountains with a purple sky."

This isn't so different from LeWitt telling an assistant: "Draw vertical lines, not touching, covering the wall."

Both provide directions and get results they couldn't completely predict beforehand.

The big difference? LeWitt's instructions always produce similar results if followed correctly. AI instructions produce different results each time. In fact with many models, if you simply hit enter from the same prompt, you will see another option.

This raises interesting questions. If I type a description that produces a beautiful image, who's the artist? Me? The AI? The people who built the AI? The artists whose work was used to teach the AI?

(There's no simple answer here.)

Digital Ownership in a Copy-Paste World

LeWitt would sell certificates with his instructions. These certificates gave owners the right to install his wall drawings according to his specifications.

This might remind you of NFTs, those digital certificates of ownership that made headlines a few years back.

Both try to create a sense of "owning the original" in a world where copies are easy to make. You can photograph a LeWitt wall drawing or screenshot an NFT image, but you don't own the official version.

It's a strange situation: these types of art are super easy to reproduce visually, yet people pay big money to own the "authentic" version.

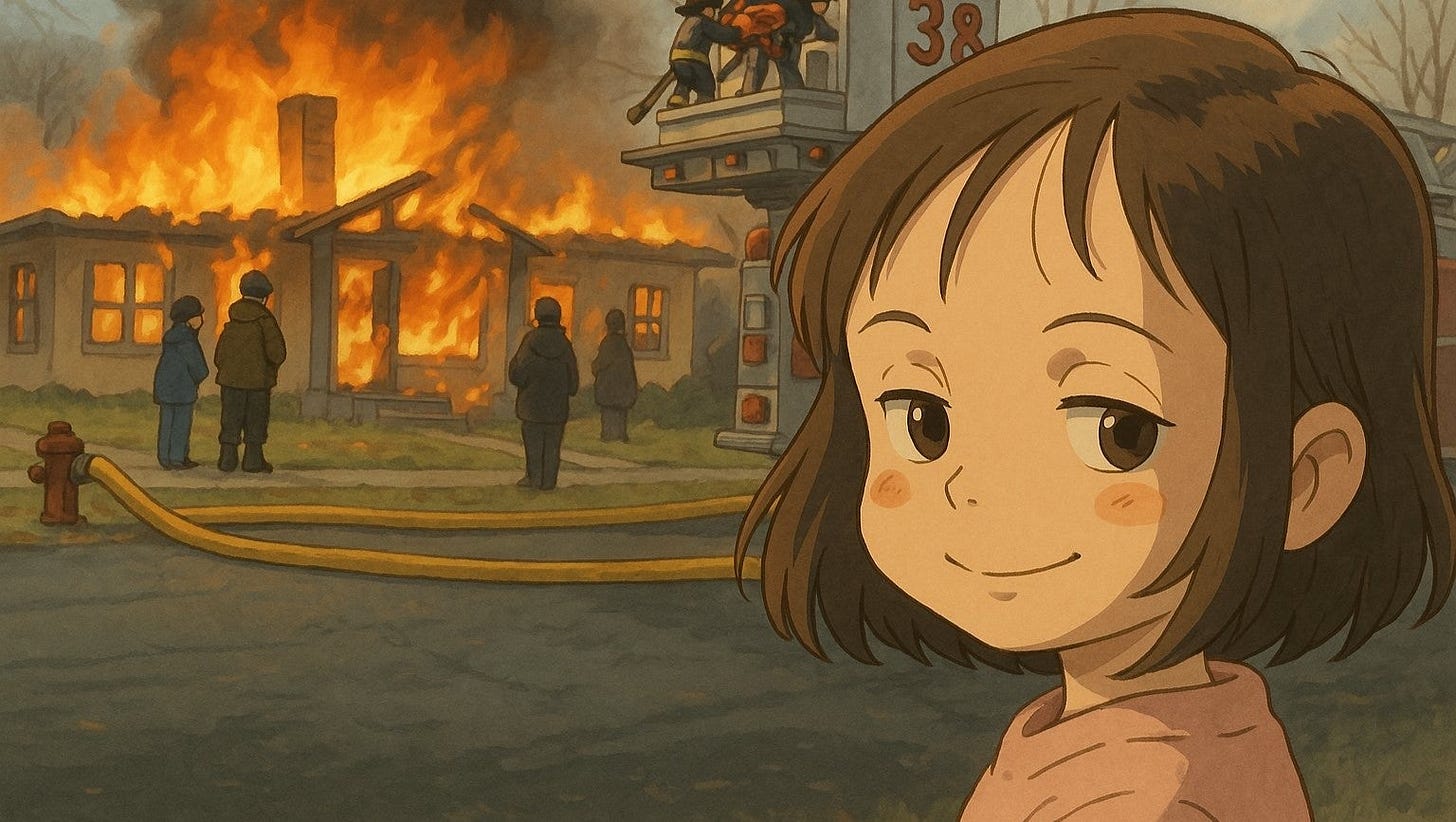

And just this month brings a controversy where OpenAI allows users to generate images in the Studio Ghibli style. Who wouldn’t want to see what Studio Ghibli animators would do if they represented you in one of their legendary films. The issue is this philosophy goes directly against the philosophy of the legendary animation studio and director Hayao Miyazaki.

So does using AI tools to mimic the style of a legendary artist honor the work or does it simply use the intellectual property?

Photography Did It First

Photography worked this way long before computers.

A photographer creates a negative. This is essentially a set of instructions for making prints. The negative contains all the information, but isn't what we see in a gallery.

Many famous photographers don't even print their own work. Someone else often makes the prints we see, following the photographer's specifications. This is just like how LeWitt's wall drawings are created by trained assistants.

When we look at an Ansel Adams landscape printed after his death, we still call it "an Ansel Adams photograph." The idea and the negative matter more than who physically made the print.

But in contrast, a few years back there was controversy around the glass artist Dale Chihuly and how, it turned out, most of the glass masterpieces credited to Chihuly were actually blown by his assistants. I love this article “If Dale Chihuly didn't personally blow that glass, do you still have a Chihuly?” which explores these same topics.

So What Does All This Mean?

These examples force us to rethink basic questions:

What's the "real" artwork? The idea or the physical thing?

Who's the "real" artist? The person with the concept or the person who makes it?

How do we value work that exists primarily as a set of instructions?

These aren't just artsy philosophical questions. They directly affect how we think about digital creativity, ownership, and value in a world where anything can be copied with a click.

Maybe LeWitt was ahead of his time. By separating ideas from physical creation, he anticipated our current situation where the lines between concept, instruction, execution, and reproduction have become super blurry.

Art has always been about ideas. But perhaps now more than ever, the idea itself—the instruction set—has become the main event.